Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

Schlitz: How Milwaukee's Famous Beer Became Infamous

The disastrous effect of deciding to reduce product quality salami slice by salami slice is now known in business circles as "the Schlitz mistake."

You might think it would be good to have your company held up in business schools as a famous example. But that wouldn't be the way the people behind the Schlitz brand feel about it. Schlitz is held up as a dreadful warning of how not to do it.

Indeed, the company that now owns Schlitz, once "the beer that made Milwaukee famous," is currently telling drinkers that "our classic 1960's formula is back," the sub-text being that it "now tastes the way it did before we started disastrously mucking about with it 40 years ago, ruining the beer and wrecking the company along the way."

Schlitz's roots were in a Milwaukee restaurant started by 34-year-old August Krug, an immigrant from Bavaria, in 1848. Two years later Krug hired Joseph Schlitz, another German immigrant, from Mainz, to be his bookkeeper. When Krug died in 1856, Schlitz took over the management of the brewery, marrying Krug's widow Anna two years later and changing the name of the business to his own. That same year Krug's 16-year-old nephew, August Uihlein, began working for the brewery. Over the next two decades the brewery grew to be one of the two or three biggest in Milwaukee. Then in 1875 Schlitz was drowned after the ship in which he was travelling on a voyage back to Germany struck rocks off the Scilly Isles. Control of the brewery was inherited by August Uihlein and his three brothers, who had joined him in the business.

The brewery prospered considerably under the Uihleins, springing back after Prohibition, and late in the 1940’s Schlitz became the best-selling brew in the United States – the Wisconsin brewer wrestling the title from Anheuser-Busch's Budweiser, the self-styled "King of Beers." The 1950’s saw a continuous assault from Anheuser-Busch to win back the crown of America's favorite. The two brewers swapped the lead between them until 1957, when Budweiser went ahead permanently. The decisions taken by the brewery's owners, the Uihlein family, to cope with their rival's dominance would eventually "salami slice" their company to death.

The result was that Schlitz was now getting much more beer out of the same amount of plant, with all the boost in margins that meant. At the same time Uihlein instructed his brewers to begin cutting costs by using corn syrup to replace some of the malted barley used to make the beer, and by substituting cheaper hop pellets for fresh hops. The ingredient alterations were meant to be made incrementally, Uihlein's belief apparently being that drinkers would not notice each slight change to the product. Unfortunately, as commentators later pointed out, the steps from A to B and from B to C might have been tiny and unnoticeable, but the steps from A to M added up to a big leap.

At first all seemed to be working. In 1973 Schlitz was able to boast that it had the most efficient breweries in the world, and it was carrying out a rapid expansion of its production capacity. Its profits-to-sales ratio and its utilization of its plant – in terms of capacity against actual production – were both substantially above the industry average. Market share was growing faster than at either of the other big two American brewers, Anheuser-Busch and Miller. Rivals tried to trip Schlitz up by claiming that its ABF brewing method meant it was selling "green," or too-young beer. Schlitz responded by changing the meaning of ABF from "accelerated batch fermentation" to "accurate balanced fermentation."

Uihlein had already been given a warning about what could happen if drinkers felt a brewer was messing about with beer quality, however. In 1964 Schlitz had acquired the Primo Brewery in Hawaii. By 1971, Primo accounted for 70 percent of all beer sold in Hawaii. Then Schlitz stopped full brewing at the Primo plant, instead shipping dehydrated wort from its brewery in Los Angeles for fermentation in Hawaii. Islanders said the taste of their favorite beer had been altered for the worse with the change, and Primo's market share dropped like a brick to just 20 percent in 1975. Schlitz started full brewing in Hawaii again that year, but sales of Primo never recovered to their previous high.

Back on the mainland, the brewery had attempted to respond to the growing success of Miller Lite, the first successful low-calorie beer, with the launch of Schlitz Light in late 1976. But perhaps because drinkers were already suspicious about what went into ordinary Schlitz, Light was a failure in an otherwise expanding sector.

Meanwhile Schlitz was running into trouble with its mainstream brand, after an attempt to disguise to consumers what it was putting into its beer. Because it aged its beer less than other brewers, Schlitz had to add silica gel to the product to prevent a haze forming when it was chilled. In 1976 the company began to worry that the United States Food and Drug Administration would compel brewers to list all their ingredients on bottles and cans. Its use of silica gel would show up in harsh contrast to its rivals such as Anheuser-Busch, who aged their beers longer, allowing the protein to settle out naturally, and therefore did not need to use artificial anti-haze products.

Anheuser-Busch was sure to point to Schlitz's use of an "unnatural" product in its beers and contrast this with the "all-natural" Budweiser. By 1967 the company's president and chairman was August Uihlein's grandson, the polo-playing, 6-foot-4–inch-tall Harvard graduate Robert Uihlein Jr., then 51. Robert decided that if he could not sell more beer than Anheuser-Busch, he would at least make his company more profitable than his St. Louis rival. The first step in Uihlein's plan to save money was a new brewing method Schlitz called "accelerated batch fermentation," or ABF. This cut the brewing time for Schlitz beers from 25 to 21 days, and then from 20 to 15 days, compared to the 32 to 40 days of storage – or "lagering" – used for Budweiser.

Schlitz decided to use another beer stabilizer instead, one that would be filtered out of the final product and thus would not have to be listed as among the ingredients. Unfortunately, what Schlitz's brewing technicians did not know was that the new anti-haze agent, called Chillgarde, would react in the bottles and cans with the foam stabilizer they also used, to cause protein to settle out. At its best this protein looked liked tiny white flakes floating in the beer and at its worst it looked like mucus, or "snot," as one observer bluntly called it.

For months Schlitz kept quiet about the problem, with Uihlein arguing that the haze was not actually physically harmful to drinkers, and in any case not much of the beer would be kept at temperatures at which the haze would form. However, drinkers did complain, sales began to drop and Schlitz had to make a secret recall of 10 million bottles of beer, costing it $1.4 million.

Around the same time Robert Uihlein was diagnosed with leukemia, dying just a few weeks later. An accountant, Eugene Peters, became the company's CEO, and a geologist, Daniel McKeithan, who was the divorced husband of a big Schlitz shareholder, was appointed chairman.

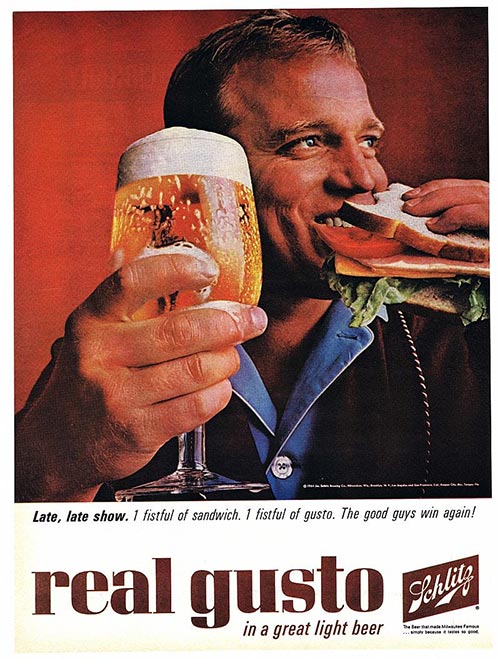

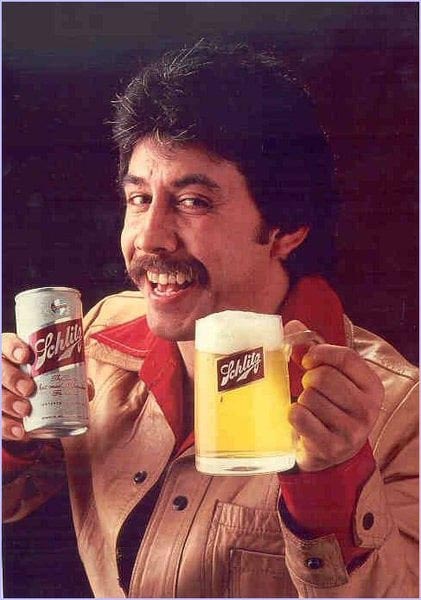

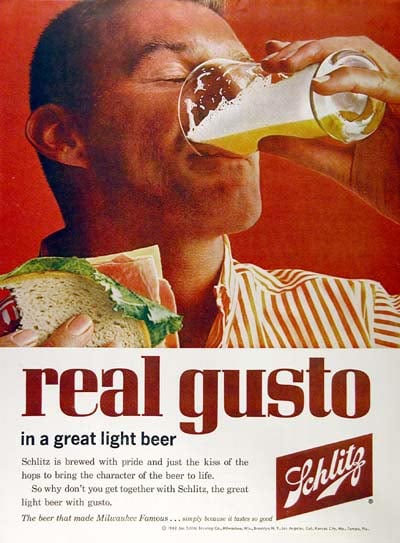

All Schlitz's problems with its image, caused by Robert Uihlein's tampering with the quality of the beer, were causing the company to start losing its second place in the American beer market to its Milwaukee rival, Miller. Even though Schlitz had increased its share of the U.S. beer market from 7 percent in 1950 to 14 percent in 1977, Budweiser and Miller had grown faster. Peters and McKeithan pushed Schlitz's marketing department to go for a new "high impact" advertising campaign featuring an aggressive-looking boxer who demanded, when asked to swap his Schlitz for another brand: "You want to take away my gusto?" Instead of amusing viewers, the ad put them off: Consumers found it "menacing," and it became known as the "drink Schlitz or I'll kill you" campaign.

By the end of 1977 Schlitz was on the slide, with profits, market share and capacity utilization dropping. Peters resigned after only 11 months and was replaced by Frank Sellinger, the former brewmaster at Anheuser-Busch. Sellinger returned to traditional brewing methods and improved the product. But Schlitz was now operating in the red, and by 1980 its sales had been passed by another Milwaukee rival, Pabst, with a third Wisconsin brewer, Heileman, not far behind.

The end came quickly. In June 1981 Schlitz closed its Milwaukee plant to try to solve what was now an overcapacity problem. In October of that year Heileman made a takeover offer for the still-struggling Schlitz, only for Pabst to put in a rival bid. Both bids were vetoed by the Justice Department on competition grounds, but in June 1982 the Justice Department allowed a $500 million bid by the Detroit brewer Stroh to go through. One analysis has estimated that the Schlitz brand lost more than 90 percent of its value between 1974 and that final year of independence.

However, the debt Stroh took on to pay for acquiring Schlitz was ultimately too much for the Detroit company to carry, and it collapsed in 1999. Ironically, in the fire sale that followed the Schlitz brand was acquired after all by Pabst Brewing Company.

The disastrous effect of deciding to reduce product quality salami slice by salami slice is now known in business circles as "the Schlitz mistake." It has been argued that Robert Uihlein's response to the increased competition from Anheuser-Busch and Miller – cutting costs to increase short-term profits – was a rational decision, and if there had been anything of a strategy of "management of decline" about it, then the complete collapse in shareholder value of the late 1970’s and early 1980’s might have been avoided.

It would have been realistic for Uihlein to conclude in 1970 that the medium to long-term future of the American brewing industry would be one where only two or three big brands would command the vast majority of sales. This is, after all, exactly what did happen, with Anheuser-Busch InBev, SAB Miller and MolsonCoors dominating the picture today. It would also have been realistic for Uihlein to conclude that, whatever Schlitz's position was in 1970, there was no guarantee it would end up as one of those surviving two or three beer giants, and it was better to go for maximum profits while allowing the company to run down gently.

However, what Uihlein tried to do was have his brewery cake and eat it too: cut costs, boost short-term profits and still maintain a long-term future for the company. The result was what the airline business calls a "controlled flight into terrain." Cost-cutting cost the company its reputation, something almost impossible to repair for a consumer goods maker, and it destroyed a concern that had once been the biggest in its field.

Comments

Pages