Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

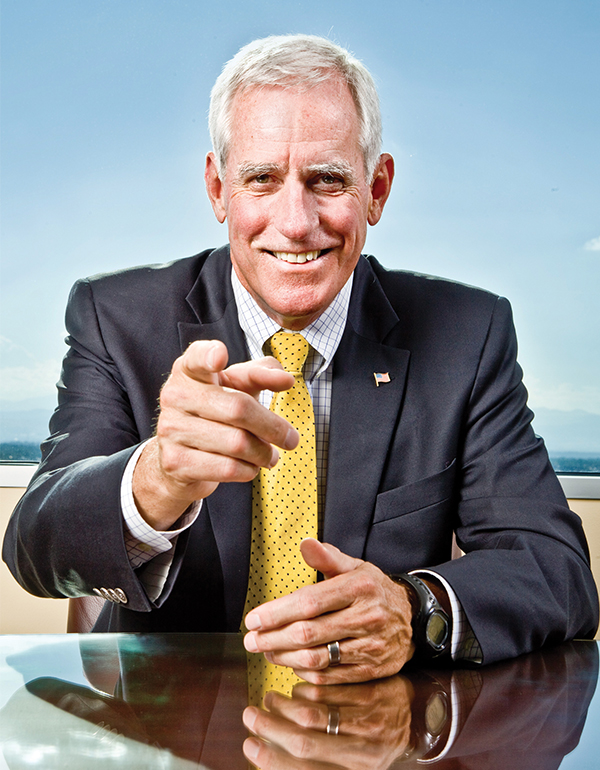

Pete Coors Talks Craft Beer

The western view from the office of Pete Coors in Denver is a spectacular vista of the rugged snow-capped peaks of the Rocky Mountains’ Front Range. “You can’t see Golden from here, but you can see the gap between the two mesas where the road goes,” said Coors.

Coors literally grew up at the family brewery in Golden, living within its confines until he was seven years old before his father finally broke the German tradition of maintaining a house at the brewery and moved to one overlooking it. “I grew up dodging trains and sneaking into the malt house,” said the fourth generation beer executive – now rugged and snow-capped himself at age 68. “You can’t do that anymore.”

In the last two decades, another aspect of life has changed that Coors is keeping his eye on. No longer can he count on dominating markets by virtue of size and efficiency. The alternating chairman of MolsonCoors and the chairman of MillerCoors, he is now contending with a bevy of smaller craft brewers who are taking market share.

‘Big brands drive velocity. When they take us off taps and put us in bottles behind the bar, we lose and the retailers lose velocity.’

One of Coors’ most recent answers to this onslaught was the creation of AC Golden Brewing Company in 2009, a small batch brewery that creates and incubates new beers for MillerCoors. Featuring the initials of Adolph Coors, who bought out his partner to create the Coors Brewing Company in 1880, AC Golden is one of the new fronts in the skirmish that has turned into a battle with craft brewers and is located in the middle of the massive Coors brewing operations in Golden.

There were signs of progress at this year’s Great American Beer Festival, where AC Golden won the gold for the Colorado Native brand’s Amber Lager and a silver medal for its Golden Lager. “U.S. beer volume is flat,” said Coors during a 45-minute visit the week of the GABF. But, brewers with annual production often below 70,000 barrels a year are taking tap handles. In a humorous aside Coors offers a back-handed compliment to these craft brewers with the hint of an avuncular smile dawning on his face. “We’re competing against a bunch of mosquitoes,” he said, his hands shifting in the air as if to emphasize the nimble and unpredictable nature of these opponents.

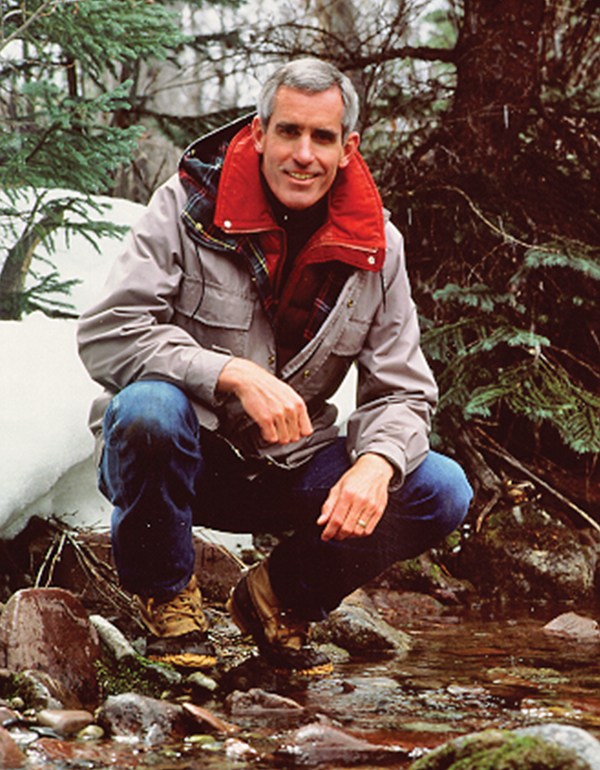

Coors and his companies, where he says there are no sacred cows, have hardly been caught flat-footed by the craft movement. Before the merger, Coors’ company dispatched young molecular biologist Keith Villa to Belgium in 1995 to get his Ph.D. in brewing science. It was a time when a new, second generation of smaller, independent American beer makers were emerging and the segment was undergoing a name change from microbrewing to craft.

Villa, who had been initially hired by Coors Brewing through an ad placed on a bulletin board at the University of Colorado in the biology department, eventually came up with Blue Moon. Contract-brewed at first and currently produced in Golden and Eden, North Carolina, the brand sells close to 2 million barrels per year according to a variety of market sources, which trails only Boston Beer Company among craft brewers.

“I tried to kill Blue Moon two or three times,” said Coors, also deft at humor at his own expense. He recalls his initial and unfavorable response to Villa and the company’s Research and Development team. “‘You tell me we’re going to put fruit in our beer and it’s going to be cloudy and it’s going to have coriander and orange peel in it?’” he said. “‘This will never work.’”

But Coors let this particular kettle continue to simmer as an underperforming Stock Keeping Unit. “It was just a pain – just another SKU,” he said. “It took 13 years for it to take off. We call it the 13-year overnight success story. We were just patient with it. We were ahead of the curve.”

Craft enthusiasts knock the flagship Blue Moon Belgian White, because it doesn’t fit the Belgian wit style and is more typical of mainstream American big brewing. Oats, which are a favorite ingredient for craft brewers but out of style in a Belgian wit, give Blue Moon more smoothness and drinkability. The sweeter Valencia orange is used in place of the tarter Curaçao version and the ABV is higher at 5.4 percent in an effort to pair Blue Moon better with food.

The over-riding emphasis on drinkability is part of the Coors tradition, one handed down from Coors’ 98-year-old Uncle Bill, who still works alongside his nephew on the drinkability panel for Coors Light. The advice from Uncle Bill comes in the form of a rather wet story with a large dose of the dry humor that seems to run in the Coors family.

“My uncle told me that if you’re mowing the lawn and decide, ‘I’ll stop and have a beer’ and then go back and finish the job, that’s not really drinkability,” said Coors. “If you have a beer and go back and do a couple more rows and decide to have another, then the beer’s beginning to get it. If you finish the six-pack before you finish mowing, then you’re really getting there. If you leave the lawn mower and go down to the corner bar and drink the rest of the afternoon, then the beer has really hit a home run.”

Starting with the Banquet Beer, drinkability drove growth. But, when Coors’ grandfather was in charge of the family business, he declared the company would not exceed 250,000 barrels per year. “He said, ‘If we get any bigger we just can’t control quality,’” said Coors. But these days, the volume produced in Golden alone, now part of a network of facilities and a division of MillerCoors, is 11 million barrels a year.

“Craft beer drinkers like to savor their beers,” said Coors. “Premium light drinkers like to drink a few.”

Coors is currently pushing the message of drinkability in the battle for taps with craft brewers, reminding retailers that drinkers of the traditional American styles tend to linger at the bar and drink more volume. “Craft beer drinkers like to savor their beers,” said Coors. “Premium light drinkers like to drink a few.”

The battle at the taps is a serious one, an area where craft is finding some advantage and an area of ongoing contention. “We create velocity in an account,” said Coors. “That’s what really drives profitability for retailers. Big brands drive velocity. When they take us off taps and put us in bottles behind the bar, we lose and the retailers lose velocity.”

Colorado Native Amber, introduced in 2010 and a silver medal winner at GABF in 2011, is another round in the struggle over taps. “What we’ve learned from the craft guys is that consumers like to have some variety,” said Coors.

The new brand, made with Chinook, Cascade and Centennial hops, is available only in Colorado, where it’s generally found in bars and restaurants serving not only craft but the mainstream brews from the brands of Anheuser-Busch, Pabst and MillerCoors. Made entirely from hops, barley and water from Colorado, the new beer demonstrates Coors can combine drinkability with a hoppier, more malty brew. New from Colorado Native, said Coors, is an IPL, an even hoppier lager that was introduced in August.

“We started Colorado Native to do things more like craft brewers and to see if we could do things on a small scale,” said Coors. Although he’s considered selling Colorado Native in other states like Texas where it would be a natural fit, Coors said no decision has been made on exporting the medal-winning brand. “If you start selling in 10 or 12 states does it lose its aura and mystique?” said Coors, whose main brewing facilities could make the volume and distribution happen quickly. “These are things that the big guys have to worry about.”

Coors gives every impression that major brewers are still very concerned about competing for market share with each other more than with craft brewers. At a meeting shortly after the MillerCoors joint venture was established in 2008, he advised executives not to worry about being polite and drinking the new joint partner’s beer. “Drink the beer you like,” he said in a speech. “The guys in St. Louis are the enemy.”

But he said “It stings a bit” when he hears that Blue Moon is “crafty,” a term that was a prominent part of a 2012 ad campaign by the Boulder, Colorado-based Brewers Association, the industry trade representative of craft brewers which also hosts the GABF. The ad was directed, in part, at the fact Blue Moon has its own Tenth and Blake Beer Company label and the name of parent company MillerCoors does not appear on it.

The Brewers Association has long corralled the smaller brewers under its banner by assigning size based on annual barrel production as the key criteria for its branding of who is a craft brewer. Coors pointed out the ceiling for craft has been raised by the BA due to the growth of Boston Beer Company. “Craft people like to say everybody who makes up to six million barrels in a year is a craft brewer,” he said. “I think that’s stretching it a bit. That was done for (Boston Beer founder) Jim Koch.”

“We started Colorado Native to do things more like craft brewers and to see if we could do things on a small scale,” said Coors.

Coors acknowledges size does matter when it comes to brewing. “One of the challenges we have – our brew kettles are big brew kettles,” he said. “Unless we get volume up to 20,000 barrels per year it’s not really practical for us. It’s not practical for us to compete against craft brewers because we’d have so much waste.” On the other hand, Coors’ company can afford to contract brew in small batches until a beer begins to sell at the needed volume as evidenced by Blue Moon’s long gestation. In addition to producing Colorado Native, expected to hit 10,000 barrels in 2014, AC Golden is a test brewery that can provide ample opportunity to experiment.

The unmistakable trend of growth by craft brewers as defined by the BA is expected by everybody in the beer business to continue. But Coors suggested the larger of the craft brewers may start taking market share from one another during the current expansion phase, which includes increased capacity and bi-coastal locations for some. “They are starting to swarm against each other now,” he said. “It’s kind of fun to watch.” While he may have a unique perspective, like the rest of the beer world Coors is paying attention to what’s going on in American craft brewing.