Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

Beer in American History

Beer runs deep in the veins of American history, coursing through the hearts, minds and livers of those who founded modern America. Lincoln once said, “If given the truth, [the people] can be depended upon to meet any national crisis. The great point is to bring them the real facts — and beer.”

Yet those “amber waves of grain” not only predate European settlement in America, but they also helped make it possible. We don’t know the degree to which Washington’s famous courage, or Franklin’s eloquence were aided by ale, but we know a quart was rarely out of arm’s reach, helping to grease the hinges of our young nation. Here we will chart a course back in time, exploring the history of beer in North America, and its role in shaping our affairs.

Native American Brewing Techniques

Long before Pilgrims began rocking at Plymouth, Native Americans in North America were brewing a gruit-like fermented beverage from maize, birch sap and water, remnants of which have been dated back to between AD 828 and 1126, courtesy of the Pueblos. The Creek and Cherokee across the Southeast used berries and other fruits, while the Huron are said to have made a simple alcoholic gruel from fermented corn, to be used for ceremonial purposes.

While beer and other alcoholic beverages were prevalent in pre-Columbian America, it would take European excess to bring alcohol consumption to a fever pitch.

Pilgrims Running Out of Beer

On the rosier side of history, Native Americans are to thank for sharing their brew recipes with thirsty Pilgrims, who landed at Plymouth Rock in 1620 due in part to a beer shortage.

A diary entry from a Mayflower passenger reads “We could not now take time for further search [for adequate land]… our victuals being much spent, especially our beer…”

As the Pilgrims established themselves, they would have enjoyed a 3-4 percent ABV beer brewed from “Molasses… well boyled, with Sassafras or Pine infused into it,” according to colonist Willliam Penn, often from a waxed leather tankard known as a “black jack.” Of course, if those ingredients weren’t on hand, there was room to improvise. Colonial beer could be made from just about anything… “pumpkins, persimmons, cornstalks and Jerusalem artichokes… with hop substitutes including wild carrot seed, coriander seed, brown sugar, horehound and wormwood,” were all employed.

No matter what raw materials were used, the drink would have been essential, not only for reliably clean drinking water, but also as an escape from the harsh reality of life with no safety net. For these reasons, colonists drank much more on average than we do today, but the beer was weaker – as little as 1 percent ABV. Even the kids drank, often a cider and molasses mixture known as “ciderkin.”

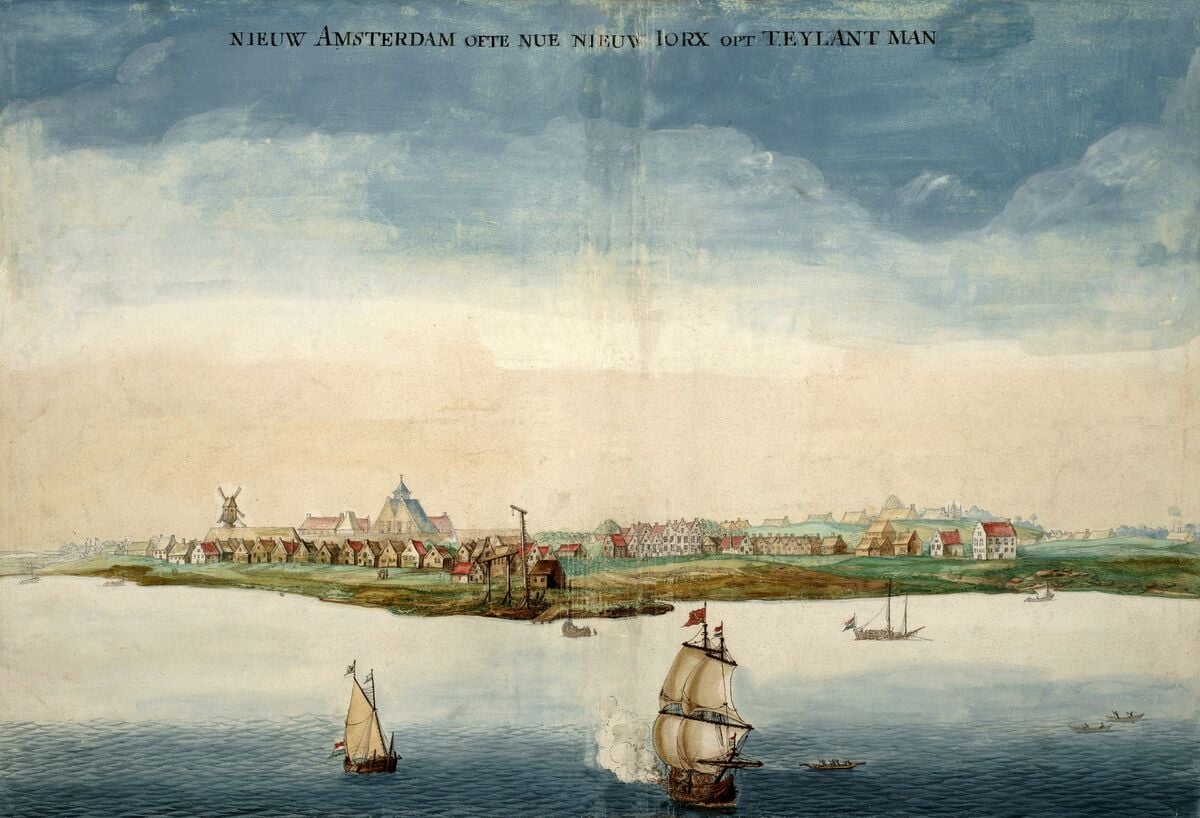

Dutch Courage

The Pilgrims were not actually the first Europeans to brew on American soil. By 1612, Dutch immigrants Adrian Block and Hans Christiansen had established the New World’s first known commercial brewery in a log house at the southern tip of New Amsterdam (Manhattan).

In 1629, the Dutch East India Company built another New Amsterdam brewery, on Brewer St. (now Stone St.), drawing water from the “Heere Gracht Canal”, which ran down what is now Broad Street, until it was filled in during British occupation in 1676.

A century before the Revolution, beer-drinking culture in America was alive and well; there appears to have been twenty-six breweries and taverns in New Amsterdam, following a well-structured system. Producers were taxed two guilders per barrel, a fee which was split between the brewer and “tapster”, or retailer. A few decades prior, the entire island of New Amsterdam had been purchased from Native Americans for just 60 guilders.

Under the governance of Peter Stuyvesant, colonists were barred from drunkenness on the Sabbath, and innkeepers could not serve “any wines, beers, or any strong waters” to anyone but travelers and boarders on Sundays -- traces of which hung around until craft beer’s most recent revolution. All retailers had to close at 9pm and couldn’t serve without a license. Even with a license, sale of alcohol to Native Americans was forbidden.

Meanwhile, beermaking followed wherever Europeans settled. Philadelphia saw its first brewery built in 1686, by a William Frampton, who was reputed to have brought the first cargo ship of slaves to the city.

From this time until the Civil War, beer production and consumption in America was largely a local affair. Storage and transport were inadequate, which meant most beer was coming from local taverns or homebrewed, which explains in part why so many of our Founding Fathers were avid beer lovers.

Founding Fathers and Beer

It is said that one of George Washington’s first acts as Commander of the Continental Army was to order that every soldier receive a daily quart of ale with his rations, a decree that would require confrontation with Congress in order to maintain as the war progressed.

Washington was a learned brewer, and was said by a friend to typically sport “a silver pint cup or mug of beer, placed by his plate, which he drank while dining.” The drink would generally have been homebrewed at Mount Vernon, and often would have been Washington’s own recipe, a handwritten copy of which can still be seen at the New York Public Library. Those who tried it said it was “superb.”

Before, during and after the Revolution, Washington and his employees would continue to brew, purchase and consume beer and its constituent parts at a steady clip. Along with wine, spirits and cider, beer was part and parcel to his daily life. And he wasn’t alone.

Most Founding Fathers, including Patrick Henry, James Madison, Samuel Adams and Ben Franklin partook and promoted America’s fledgling industry, recognizing its integral role in the formation and stability of young America. Homebrewing became a point of patriotic pride, and taverns became the social hub of revolutionaries -- a place where tough, spirited conversations could be had, and courage could be mounted.

Ben Franklin brought back a particularly enjoyable spruce beer recipe from his tenure as French ambassador, a form of which is still brewed by Yard’s in Philadelphia. Thomas Jefferson was even said to have composed a draft of the Declaration of Independence over a draft of ale and would continue to experiment with brewing at Monticello after his presidency.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a Framer who didn’t enjoy tossing a few back, save for Alexander Hamilton, whom was referred to by John Adams as an “insolent coxcomb” who became “silly and vaporing” if he drank anything more than coffee.

The firm establishment of the American brewing industry emboldened the Framers, who called for a boycott of English beer imports in 1770, further pushing America towards independence. When the last British soldiers left American soil in 1783, Washington celebrated with his officers at New York’s Fraunces Tavern.

Beer Booms in the 19th Century

By 1810, there were roughly 140 breweries producing around 180,000 barrels of beer annually, though most remained small-scale. Nine years later, a steam engine was installed at Frances Perot’s brewery in Philadelphia, the first of its kind to be used for beermaking purposes. As the Industrial Revolution gathered steam, so too did means of beer production and transport, ushering in the means to support large brewing operations.

1829 saw the founding of D.G. Yuengling Brewery in Pottsville, now the oldest operating brewery in America. What would eventually become Pabst began in 1844, followed by Schlitz in 1849 and Anheuser-Busch in 1852. By 1860, there were over 1260 breweries producing over 1 million barrels of beer for a population of 31 million, mostly in New York and Pennsylvania. Brewing had entered a new era, and would continue its meteoric growth, peaking at 4,173 breweries in 1873. Improved manufacturing would see beer production continue increasing to more than 60 million barrels as the number of breweries dipped to 1568 by 1910. Consumption increased dramatically during this time, from under four gallons in 1865 to 21 gallons in the early 1900s, and rail transport enabled breweries to sustain production on a national scale.

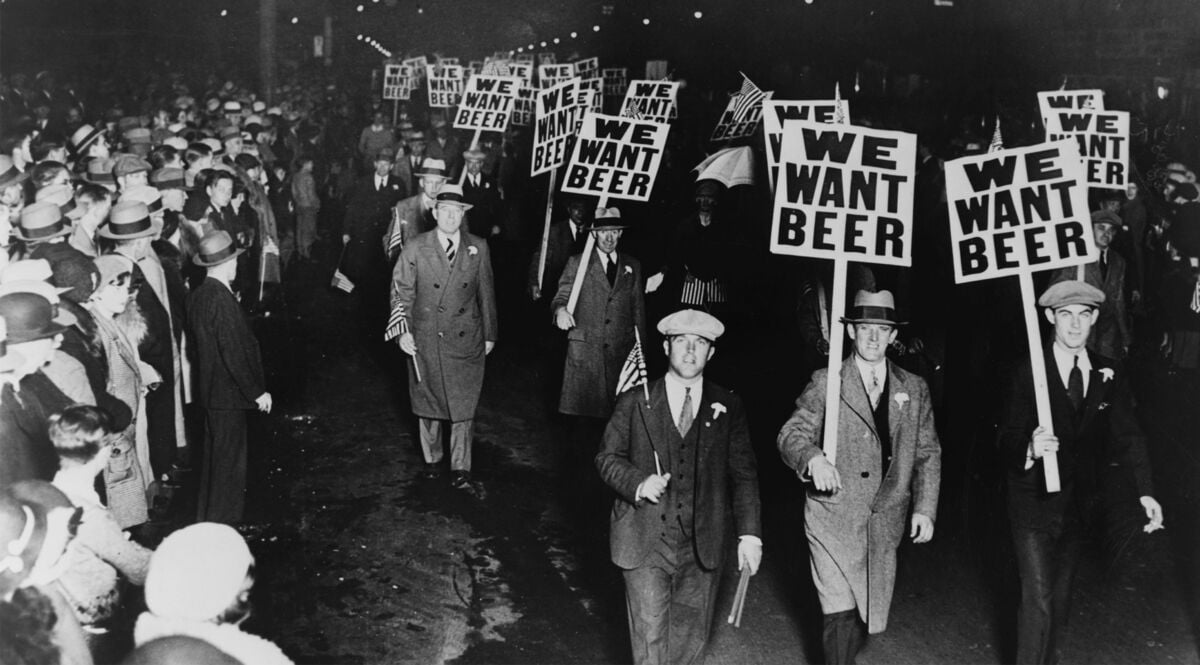

Prohibition Hits Beer Hard

Total beer production increased from 3.6 million barrels in 1865 to over 66 million barrels in 1914. By 1910, brewing had grown into one of the leading manufacturing industries in America. Yet, this increase in output did not simply reflect America’s growing population. While the number of beer drinkers certainly did rise during these years, perhaps just as importantly, per capita consumption also rose dramatically, from under four gallons in 1865 to 21 gallons in the early 1910s.

If 21 gallons seems a bit excessive to you, the Temperance movement would be inclined to agree. Social and political pressure began to mount to curb alcohol consumption, culminating in the infamous Volstead Act, which enforced the newly ratified Eighteenth Amendment. All of a sudden, production and distribution of alcohol stronger than one-half of one percent was outlawed.

Of all alcohol industries, beer was hit the hardest. Spirits had the help of legal loopholes, “prescriptions” and utility as solvents, cleaners and munitions, while the wine industry could make sacramental wine, and cideries benefitted from a laissez-faire attitude amounting to “apples are going to ferment no matter what.”

Options for breweries were limited, and about 60 percent of the nation's breweries would shutter during the thirteen years of Prohibition. Those that remained open were able to pivot to dairy products like cheese or ice cream, or stayed afloat with near beer production, or malt syrup. But the damage was compounded by the Great Depression and two World Wars. It would take decades to recover.

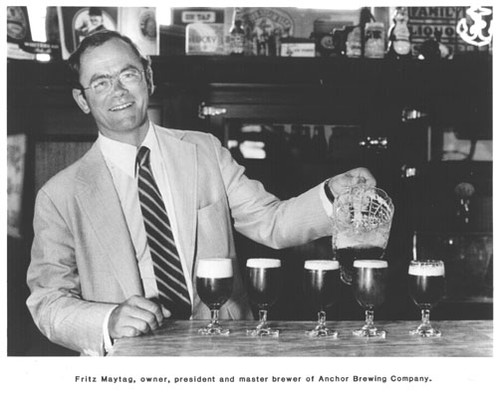

The Revolution Will Be Well Attenuated

Enter Fritz Maytag, who purchased the failing Anchor Brewing Co. in 1965, investing in production and cleanliness. Great beers, including the legendary Anchor Steam, began paving the way for modern craft brewers. New Albion, known by many as the first true American craft beer brewery, would follow, fittingly on the bicentennial, and two years later, Jimmy Carter would sign H.R. 1337 into effect, making homebrewing of beer and wine legal for all adults. The rest, as they say, is history.

Is there anything that history can teach us as we careen into the chaos of post-2020 civilization?

For starters, there is value in sitting down with a good pint and having spirited dialogue, perhaps even treading beyond the bounds of what is considered socially acceptable. In doing so, conflict gives way to resolution; impasses become ways forward. A mind loosened with libation might think more innovatively and speak more boldly. A creative, communicative society -- or Congress -- a couple beers removed from political correctness might be just the prescription our nation needs to find a way back together, so that we might move forward.

As John Adams wrote in a letter to his wife Abigail:

“Posterity! You will never know, how much it cost the present Generation, to preserve your Freedom! I hope you will make a good Use of it.”

As a matter of fact, we do have an idea of how much it cost the Founding Fathers to preserve our Freedom. Two days before signing the Constitution, the 55 delegates of the Constitutional Convention met at the City Tavern and drank “54 bottles of Madeira, 60 bottles of claret, eight of whiskey, 22 of porter, eight of hard cider, 12 of beer and seven bowls of alcoholic punch.” In total, it cost about $17,253. Let’s get to work.