Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

How To Craft a Barrel

The Art of Coopering Part 3

So here we are. We have an idea of what it takes to become a cooper, and we’ve examined foudriers, the “aristocrats of the trade,” in the words of Dick Cantwell.

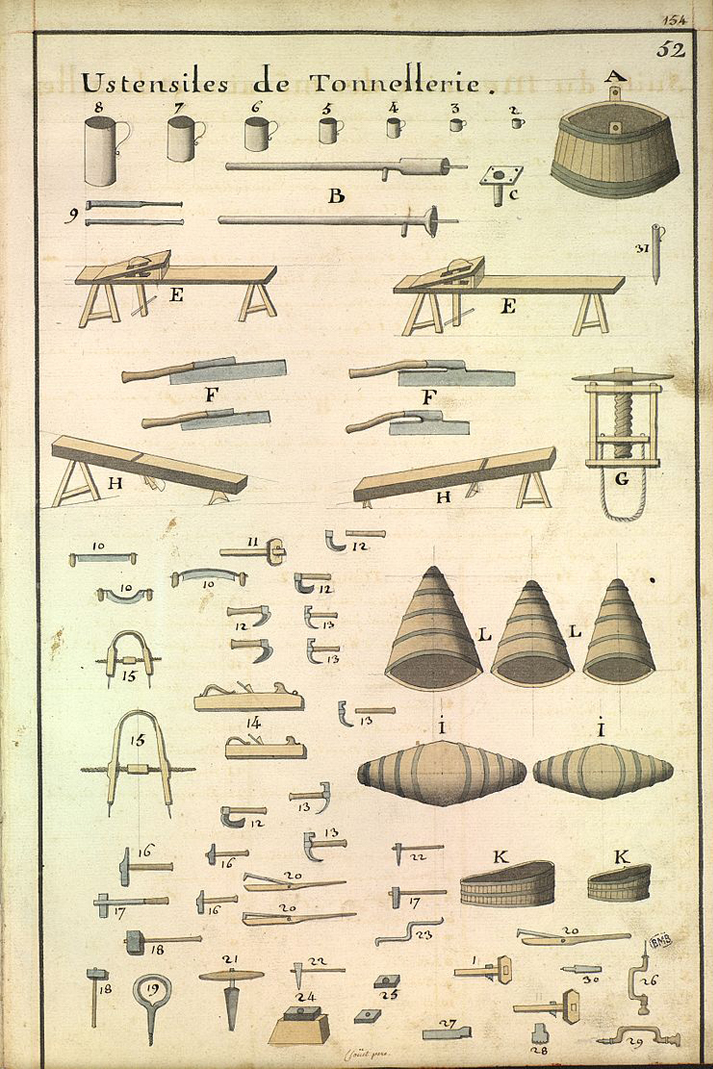

But what sort of Jedi mastery does it really take to craft a barrel? What are the tools? What do they do? And what does the wood do to the beer? Let’s find out.

The Cooper’s Arsenal

As we know, coopers are a rare bunch. They’re able to handle rough, taxing physical labor without faltering more than a thousandth of an inch during measurement-taking, sawing, shaving, fitting, hammering and more.

But before hand tools enter the equation, it starts with one of our most primitive, and powerful tools: the eye. Which tree is going to produce the best wood for barrelmaking? There are usually arborists whose entire profession revolves around cultivating and harvesting the wood needed for barrels, but a well-trained cooper can find what he or she needs: Is it straight, tall, thick, and ready for “seasoning” – where it will be aged for a number of years, generally open to the elements? If so, it's time to harvest, removing a wedge from the tree in the direction it is aimed to fall, often with lines to help guide, sometime between December and March, as that's the time when trees are least moist, and easiest to fell.

Branches are removed, and the appropriately sized and grained pieces between the trunk and top are cut in stave-sized sections, also called bolts.

Again, the cooper will generally step in a bit later in the process, but any self-respecting cooper will have an array of saws and axes, for splitting, chopping and cutting in any other format, the wood he needs, and more likely in a different era, would do so.

Once gathered, wood will be fashioned into staves. These days, laser guides will help the cooper carve the wood into its most perfect shape. Any sign of rot, infestation or physical weakness could result in discarding the wood, in which case it would be used as fuel for the flames that will eventually char the barrel. Occasionally, bullets, shrapnel and other unexpected objects will be unearthed, buried for decades within the trunk of the tree.

After being gathered and seasoned in a lumber yard, which naturally dries and tempers the wood, it’s time for the cooper to get to work.

Chisels, knives and planes can all be used to carve a stave to the exacting specifications required for barrelmaking. From Wood & Beer:

Chisels, knives and planes can all be used to carve a stave to the exacting specifications required for barrelmaking. From Wood & Beer:

“Loosely put, more wood is removed toward the center of the inside of the stave and from the ends of the outside. Already the curve of the stave is prefigured.”

A sample of the variety of tools an old-world cooper may use to craft a barrel.

Depending on the size and aim of the cooperage, this process will be done by eye or circular machine planes. Regardless, the cooper has the final say on which staves will form a barrel.

Next, the edges are jointed, formerly by hand, and now with help of a power jointer. Again from Wood & Beer, the process is described as: “smoothing the surfaces and angling them to accommodate the dual curvatures of the barrel, above all to provide a tight joint where the staves are to meet.”

The next step is considered a form of artistry by some – raising the barrel. This process involves arranging the staves in a manner which allows them to be placed in a temporary iron hoop, which holds the rough shape of the barrel until it can be fixed in a more permanent form.

This was often a two-person job, but it’s possible for a single skilled cooper to complete the task. In modern cooperages, Cantwell describes staves being placed in the “cabled loop of a windlass,” which mechanically tightens -- allowing the hoop to be placed on easily, and speeding the process significantly. Chalk is also sometimes used to help guide the hoop onto the staves.

Once one hoop is on, the barrel staves are flipped and another hoop is placed on, undoubtedly with less trouble than the first. The next step calls for fire – but not before ensuring that all excess wood particulates and rubbish is vacuumed or otherwise disposed of, as fire hazards are a constant risk.

Modern coopers hard at work in Scotland's Speyside Cooperage. (Photo by Christoph Strässler)

Toasting, aside from providing the character of the barrel as mentioned in part one, is sometimes used to help bend the wood – more often in cooperages that rely more on handcraft than machinery. To this end, sometimes wood is steamed as well, in order to facilitate bending.

Toasting equipment calls for cressets – small braziers, which the barrels are placed on top of, allowing the fire to get straight to work inside the barrel. Naturally, water becomes a necessary tool, in case things need to be doused in a hurry.

All this and we’ve only got a barrel with no heads. Back to Wood & Beer for a concise description of the process of adding heads:

“Short planks are joined together by pegs or joints, and sometimes with glue… Plotting of planks is often aided by lasers, and the heads are cut round and then planed, with bevels cut top and bottom to aid in fitting into the groove, or croze, cut within the barrel.”

In the past, knives or handsaws would do the job, but of course, these days, automation is better.

Once the heads are toasted and place on the barrel, its time for a final hooping job. A “head puller” aids in this regard, which is a piece of hooked metal that holds the head while pulling it into position.

Sophomoric entities beware, because at this point, the bunghole is ready to be drilled, or cauterized with a special “bunghole cauterizer.” It’s as hot and potentially dangerous as it sounds.

Next up is pressure testing, which involves adding a couple liters of water and applying mild air pressure to check for leaks. If any are found, they are plugged with oak shavings and hammered into place before being shaved down, these days with a belt sander. By this time, the barrel is essentially ready for use, and plugged with a temporary silicone bung.

Stay your chortling, because this is where the real fun begins. The barrel is ready to be cleaned and then filled with delicious beer.

The variety and depth of flavor wood can add to beer depends on a variety of factors, from length of time spent in the barrel to the permeability of the wood. Essentially, no two barrels will produce exactly the same beer. (Photo Credit: Allagash Brewing)

What can a barrel do to beer? Just about anything, from imparting tannins, notes of clove and marshmallow, to actually increasing the alcohol content, in the case of a previously used barrel. For more, check out part one if you haven’t already.

Now you should have an idea of what it takes to be a cooper, from the mentality to the tools required, along with a general view of the marketplace. It’s not the booming industry it once was, but if you’re craving a hands-on profession with noticeable results it may be worth further exploration.

Read The Art of Coopering Part 1: The Role of Coopering in Barrel-Aged Beers