Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

Offensive Representations on Beer Labels: Why Do They Keep Happening?

One of the great strengths of the craft beer industry is its playfulness. You see it in the way brewers are always experimenting with new ingredients to create unlikely new brews. You see it in breweries’ enthusiasm for creative collaborations. And you see it in the extraordinarily vibrant and witty artwork splashed across the results of those experiments and collaborations.

This playfulness has seen the craft beer market boom in recent years. Estimated at $110 million in 2019, this market is expected to reach $200 million globally by 2026, according to market research organization Facts & Factors.

There are moments, however, when playfulness is taken too far; when enthusiasm for a new idea gets in the way of properly thinking it through. It’s in these situations that mistakes can be made; mistakes that, unfortunately, can have public relations repercussions for brands big and small.

“Every couple of months we get some emails – angry, annoyed, concerned, something like that – saying somebody is misappropriating some Hindu symbol, imagery, deity on a beer label,” says Mat McDermott, senior director of communications at the Hindu American Foundation (HAF), an educational and advocacy organization that promotes understanding of Hindus and Hinduism. The majority religion of India, Nepal and Mauritius, Hinduism has approximately 1.2 billion adherents around the world, including 1.4 million in the U.S.

“When this happens, we reach out and point out the community views,” McDermott goes on. While Hinduism has no blanket ban on drinking alcohol and many practicing Hindus do drink, the practice is frowned upon by some Hindu traditions. Use of sacred iconography by breweries – putting an image of the elephant-headed deity Ganesh on bottles of India Pale Ale is a very common example – is therefore regarded as offensive by some.

Norway-based homebrew producer Holmentoppen Bryggerhus raised hackles with the release earlier this year of Frankie Goes to Bollywood, a kit enabling customers to create a West Coast IPA at home. A pun on the eighties British band Frankie Goes to Hollywood, it featured an image of Ganesh with a mic in one hand and a record in the other, an image Nevada-based Hindu statesman Rajan Zed called “highly inappropriate” in a statement released in June.

Holmentoppen withdrew the kit immediately, apologizing to Zed for the misstep. “The Ganesh DJ illustration seemed to go well with the name. We found it somewhere on a public domain illustrations site,” recalls Kurt Haugen, the brewery’s owner. “We made a mistake with Ganesh and will be more careful in the future.”

While Hinduism has no blanket ban on drinking alcohol and many practicing Hindus do drink, the practice is frowned upon by some Hindu traditions – putting an image of the elephant-headed deity Ganesh on bottles of India Pale Ale is a very common example.

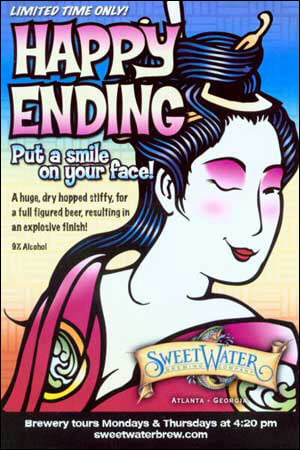

Of course, it’s not just around religion where craft beer businesses need to step carefully. There have been myriad examples of breweries causing offense with product branding over the years, from the Canadian brewery Hell’s Basement being called out in 2020 for accidentally naming its New Zealand Pale Ale a Maori word meaning ‘pubic hair’ (apparently they were aiming for ‘feather’, the other meaning of ‘huruhuru’); to Happy Ending, from Atlanta’s SweetWater Brewing Co., which got flack for its label, featuring a Geisha and a box of tissues, which some saw as sexist and racist.

The best response to such complaints, says Brian Anderson, head of advertising agency The Perception, is a prompt and fulsome apology, followed by an explanation of how the situation will be rectified:

“Saying and doing the right thing, and not trying to fake it and hide behind something, is always the smart thing. All humans have made a mistake before, so if there’s a mistake that was made from not understanding something first, just apologize for it, make the change to make it better and move forward.”

As far as avoiding such errors in the first place, it’s simply a matter of being culturally aware, Anderson goes on: “We live in a society hyper aware of every nuance, so really making sure that this is not going to be offensive to anyone is really important.”

For those in charge, canvassing for a range of opinions is key. “Every brand embodies the employees so getting a sense of how we feel about the brand before pushing that out to everyone else. How do we make sure that we represent what we believe internally, externally?” says Anderson.

Dodging accusations of cultural appropriation is also easy to do with a little forward planning and an approach to representatives of the faith or culture in question. Anderson recommends contacting “the closest community that you can reach out to – ‘How else can we say this, how else can we do this, that’s not offensive to you?’

Canadian brewery Hell’s Basement was called out in 2020 for accidentally naming its New Zealand Pale Ale a Maori word meaning ‘pubic hair’ (apparently they were aiming for ‘feather’, the other meaning of ‘huruhuru’).

“It’s a very simple phone call to make and find out. There are people out there that will answer that question pretty easily.”

Mat McDermott of the HAF agrees. He was receiving so many complaints about Hindu imagery on products – not just beer, but across multiple sectors – that a couple of years ago he published guidelines for the commercial use of Hindu images on the HAF website. As the guidelines state, it’s not just about not offending anyone, but being “culturally respectful” in general.

This is not to say that beer businesses can’t have fun with their branding. They just need to have joined the dots in terms of a supporting narrative, believes Nick Law, who runs Hop Forward, a U.K.-based creative agency for the beer industry.

“If there's no supporting narrative to explain what the true intent of it is, if it's just a beer out there, people will look for the narrative and they'll fill in all the blanks,” he explains.

Law cites the example of Gweilo, a brewery founded in Hong Kong in 2015 that launched in the U.K. last February and is planning to go stateside soon. ‘Gweilo’ is a Cantonese word for ‘foreigner’ that translates literally as ‘ghost man’. Once a slur – it dates back hundreds of years to the days of white colonial occupation of Hong Kong – today it’s merely a slang term, one that the white founders of the brewery embraced when they were first setting it up.

Sean Robertson, Gweilo’s U.K.-based commercial director, describes the lengths the founders went to in ensuring their playful adoption of the once pejorative term wouldn’t be read as offensive or flippant. “We've made it an absolute mission from day one to make people understand the phrase, the name,” he says, pointing out that they even contacted the Oxford English Dictionary to have ‘gweilo’ officially redefined. The fact that Cathay Pacific Airways, Hong Kong’s flag carrier, stocks Gweilo beer, seems to be evidence that they’ve succeeded in that mission.

Getting it wrong is inexcusable, believes Robertson. “Every business has an absolute responsibility to do their due diligence. I feel intensely that you're there to be all-embracing, genuinely transparent; that your own in-house work culture is reflective of that diversity and understanding.”

SweetWater Brewing Co. in Atlanta, Georgia received flack for its Happy Ending label when it was released, which featured a Geisha and a box of tissues, which some saw as sexist and racist.

Comments